HIROKI KATAYAMA

1937-1993

Audio design by EUCADEMIX (Yuka C. Honda)

Featuring Aki Kinoshita & Nels Cline

INTRODUCTION

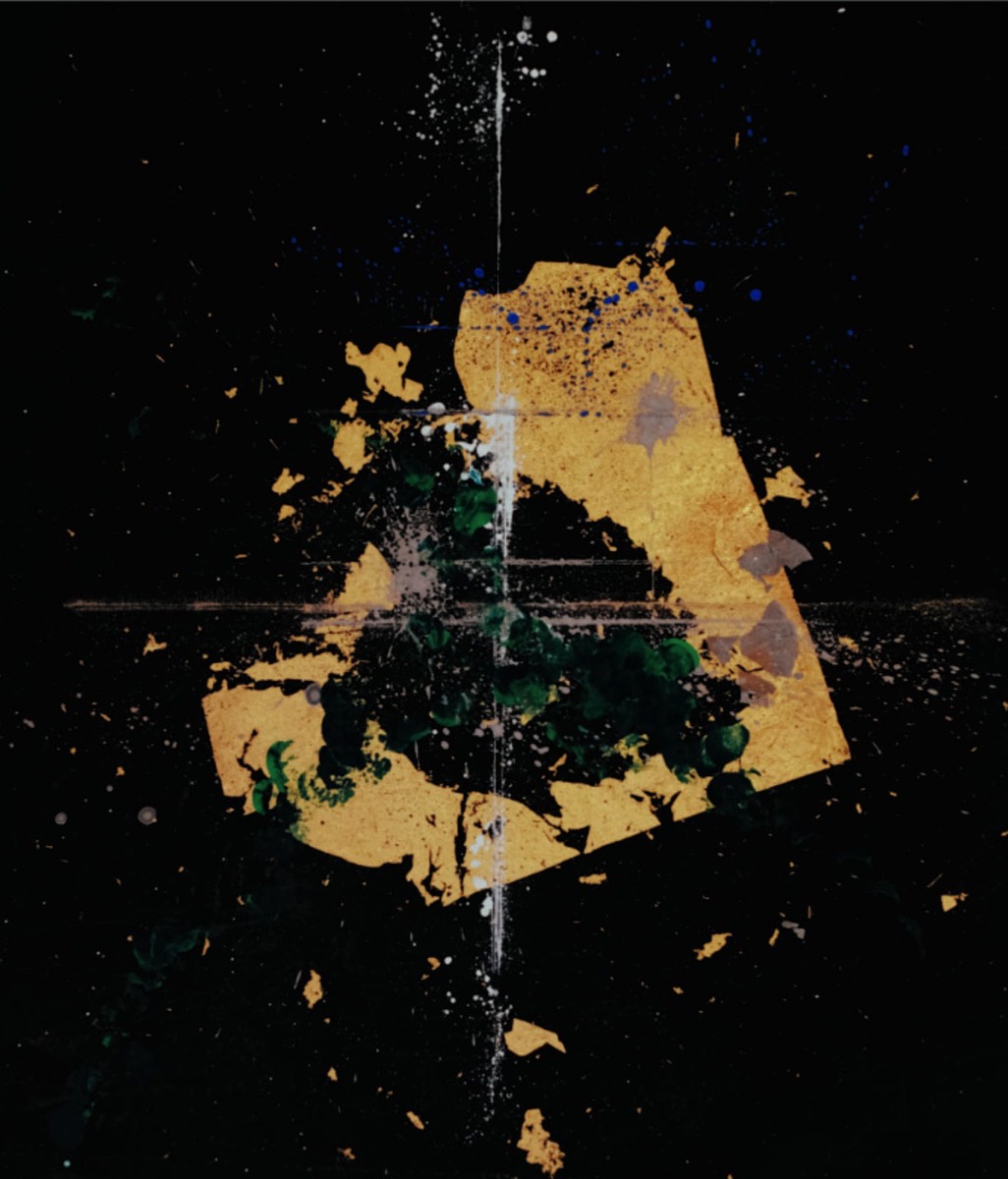

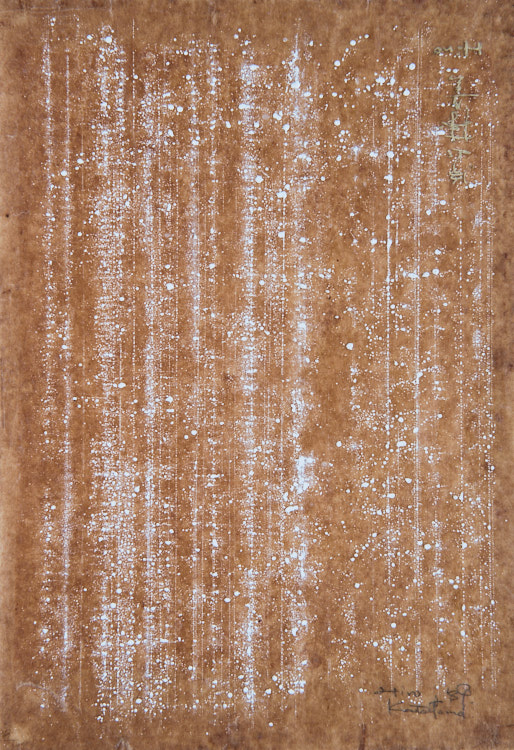

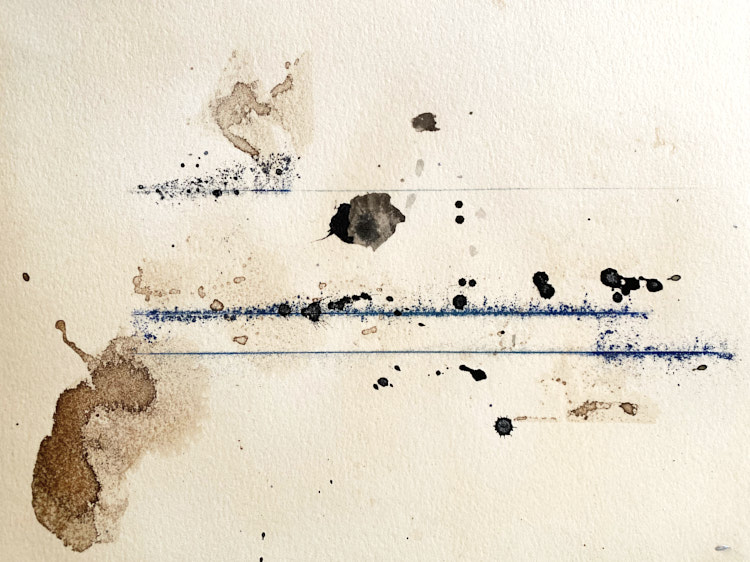

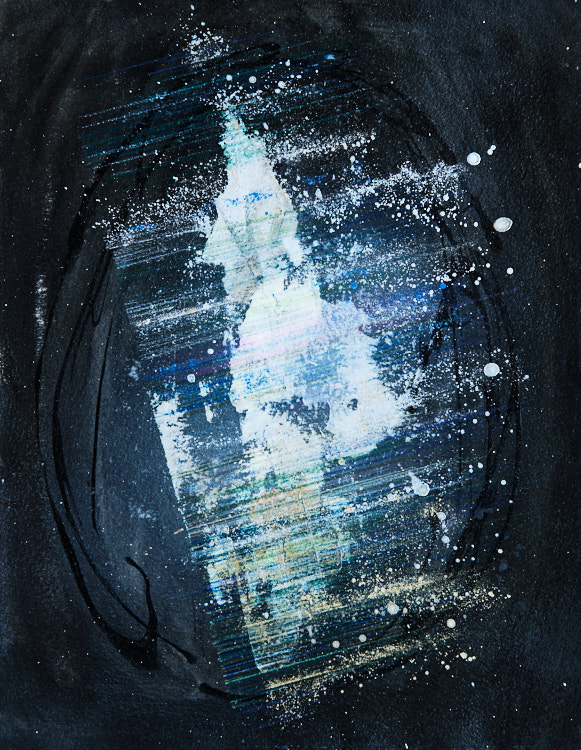

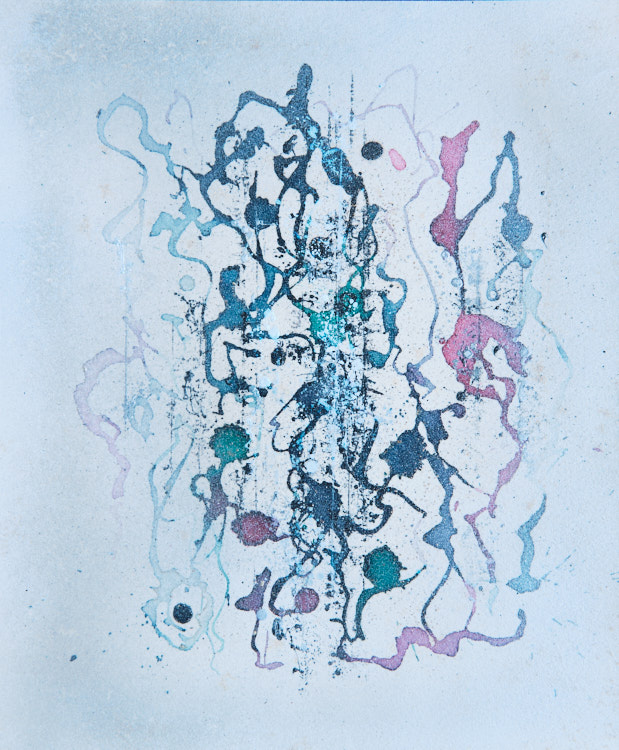

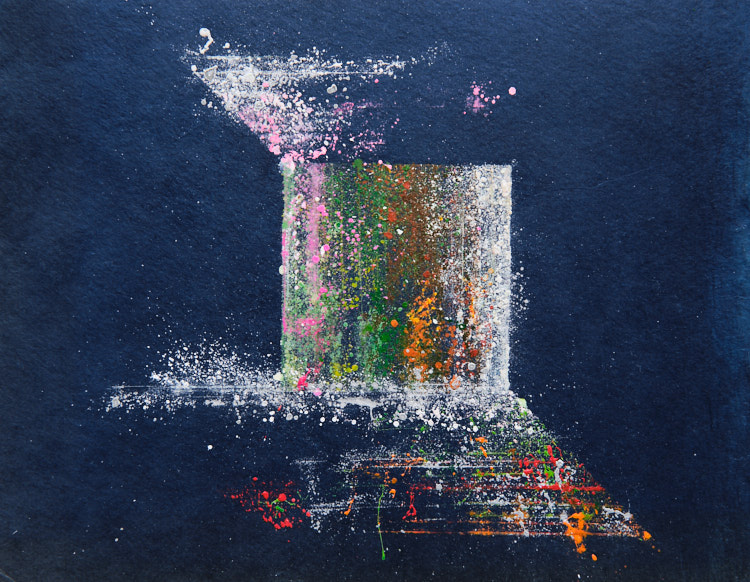

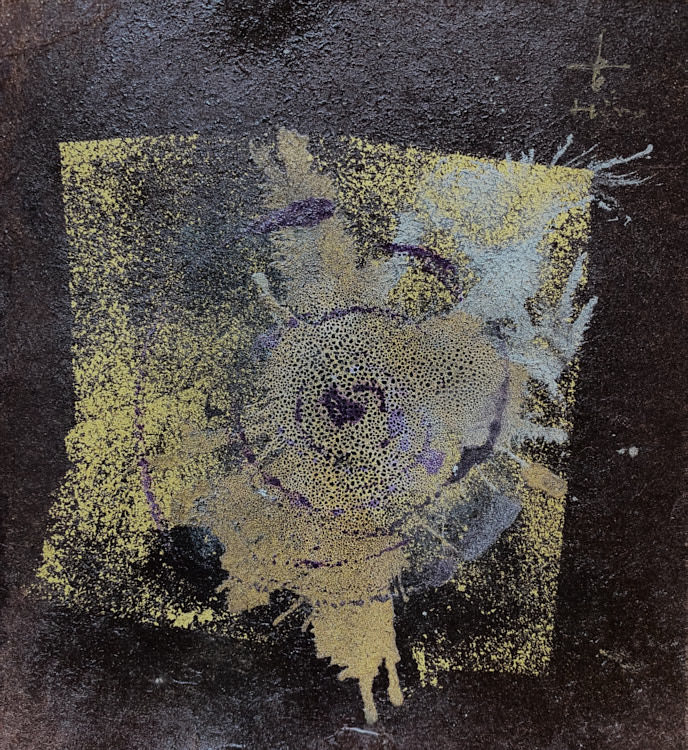

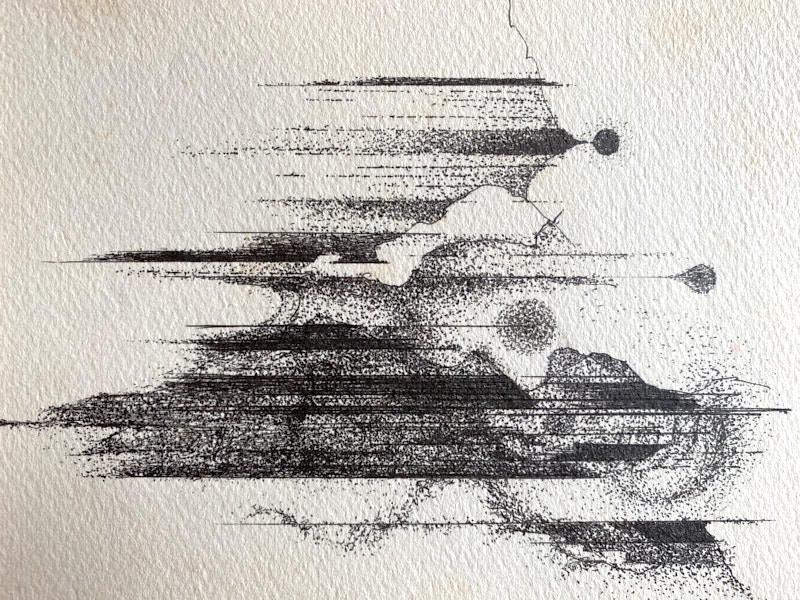

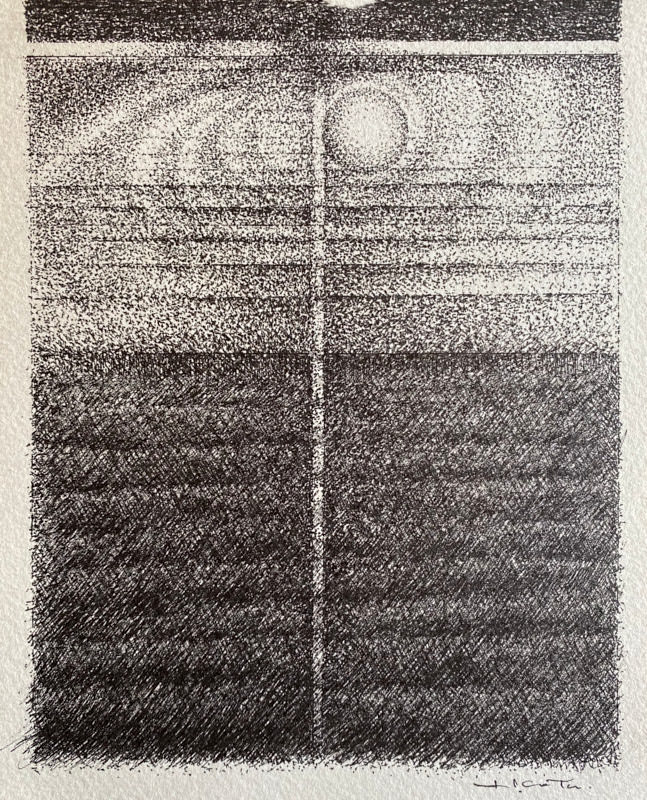

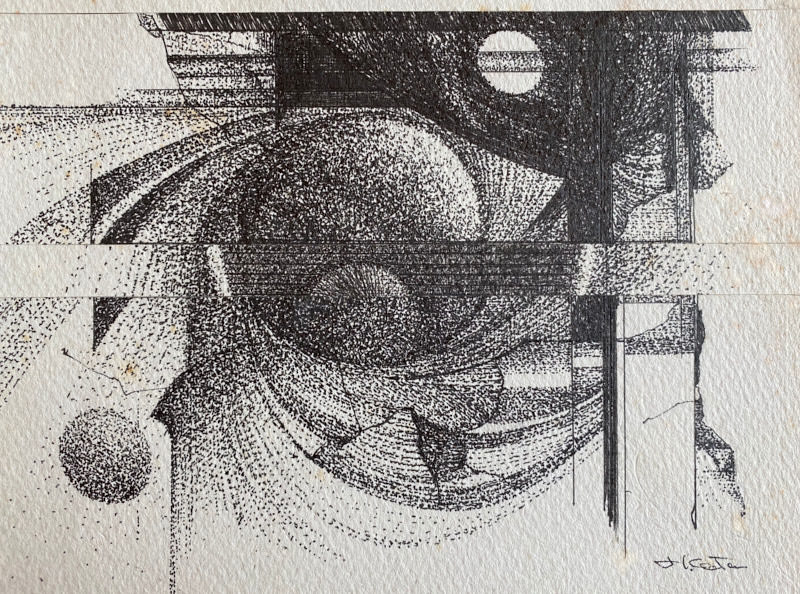

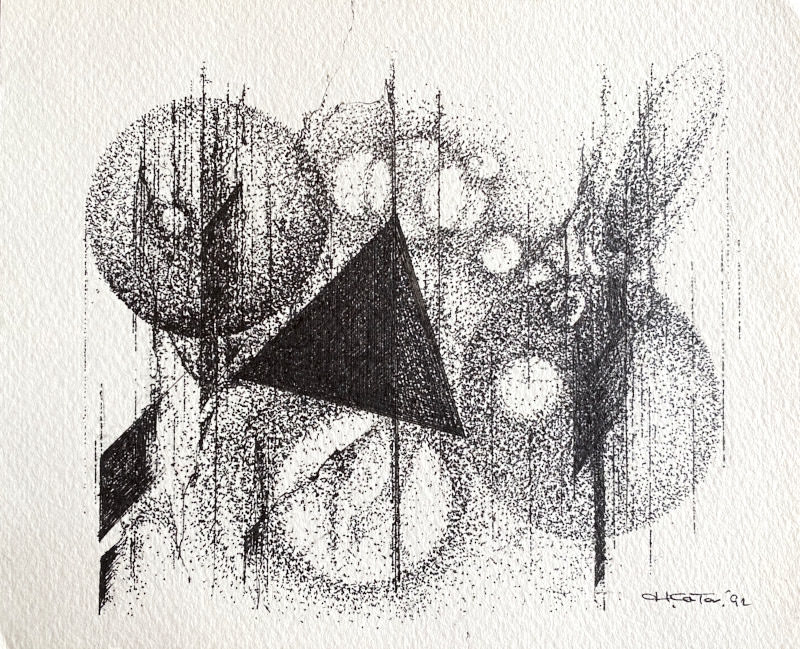

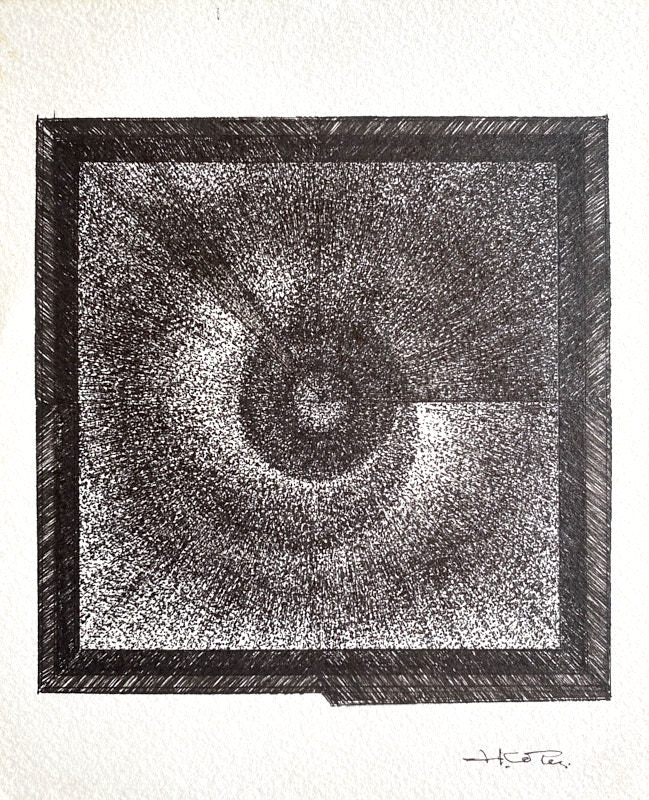

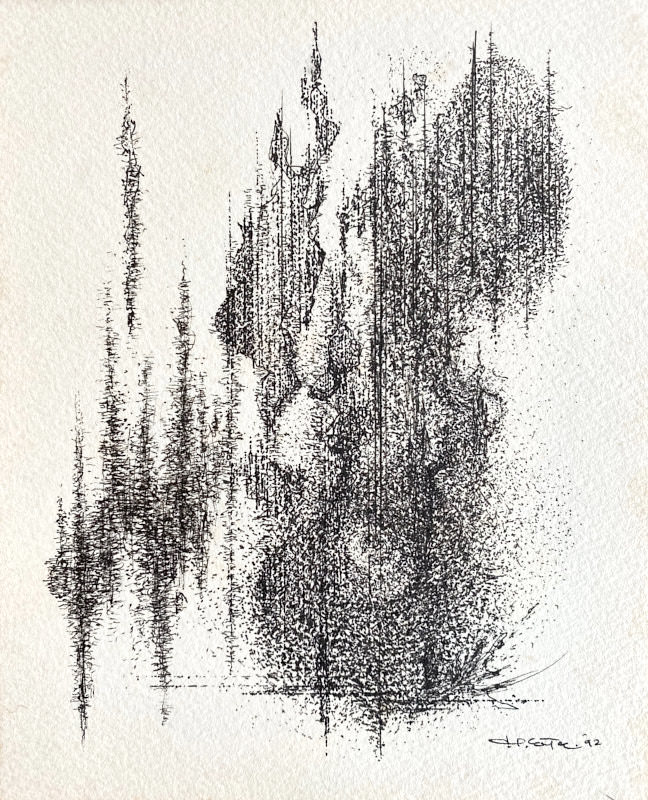

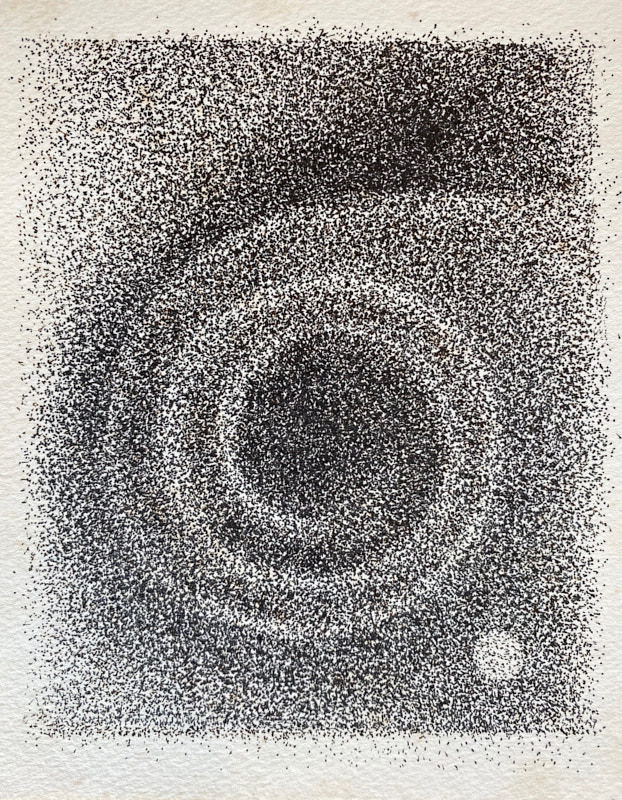

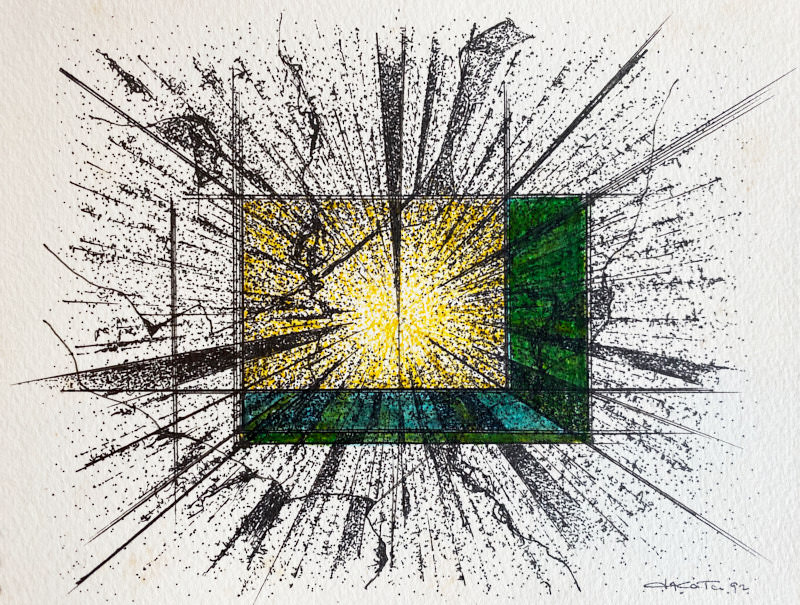

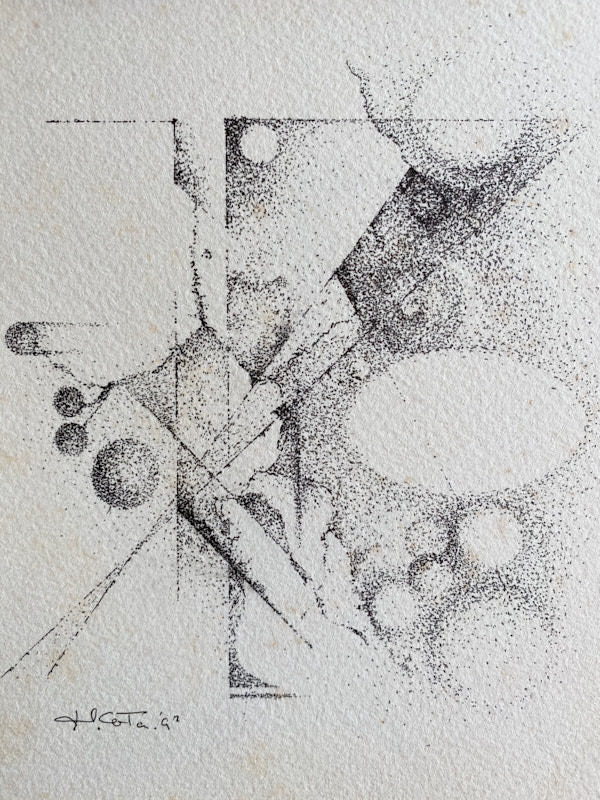

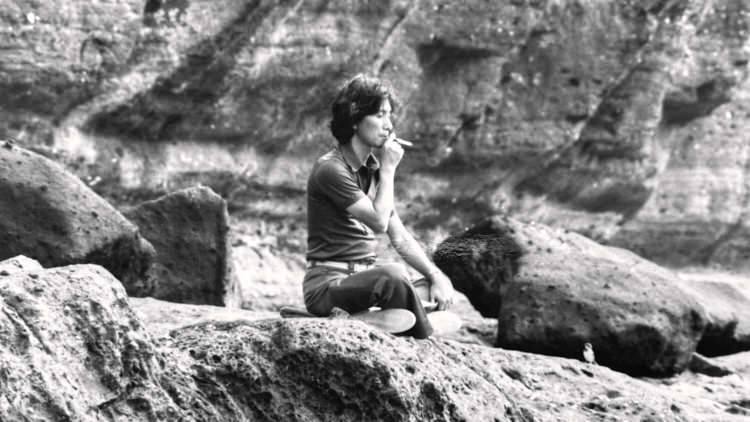

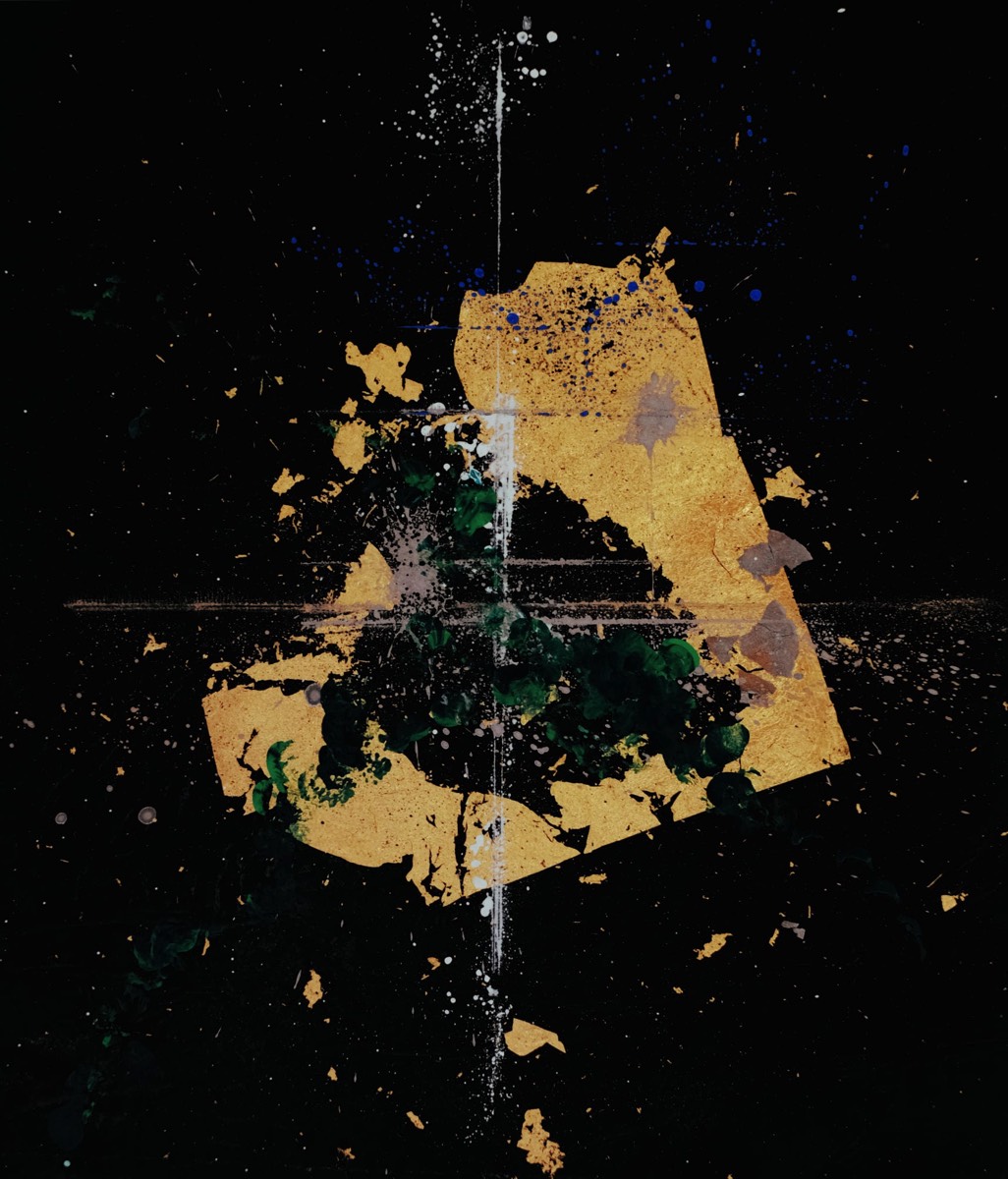

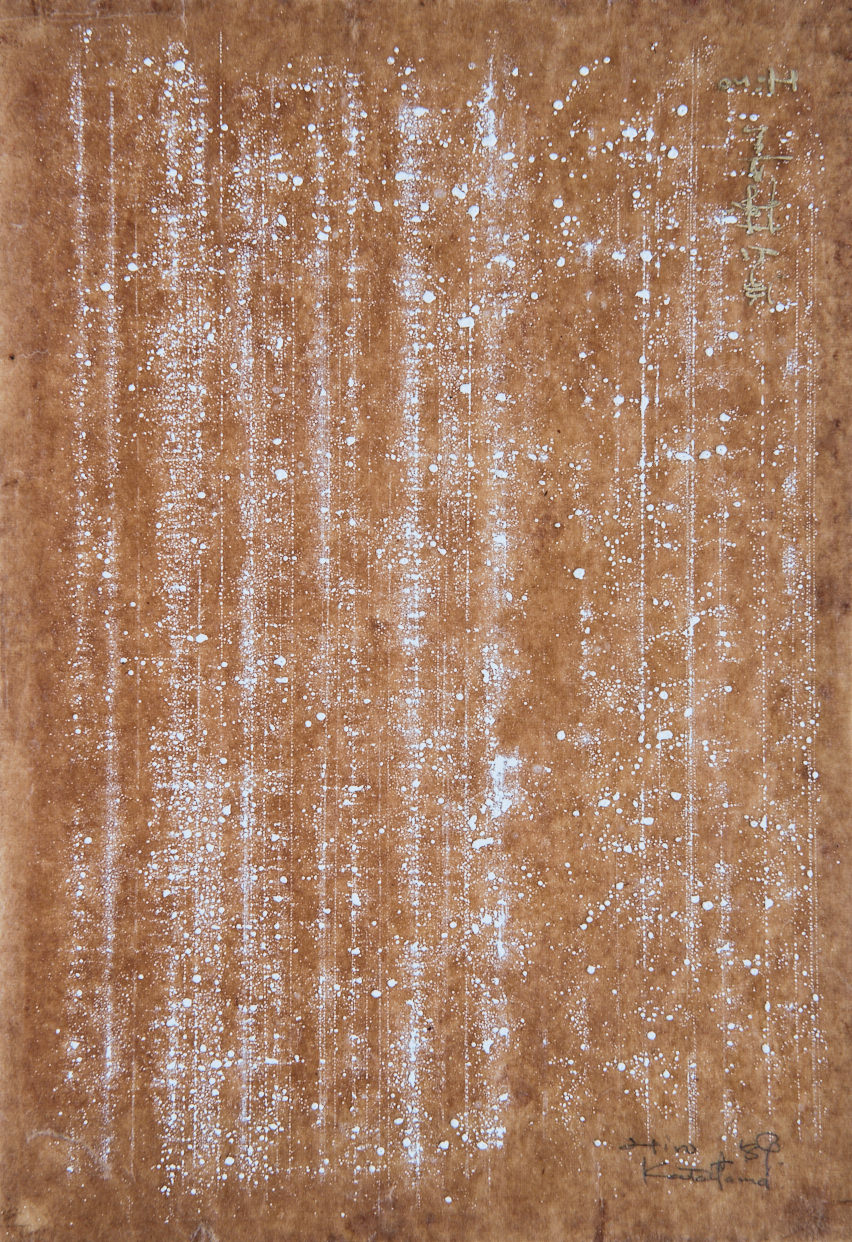

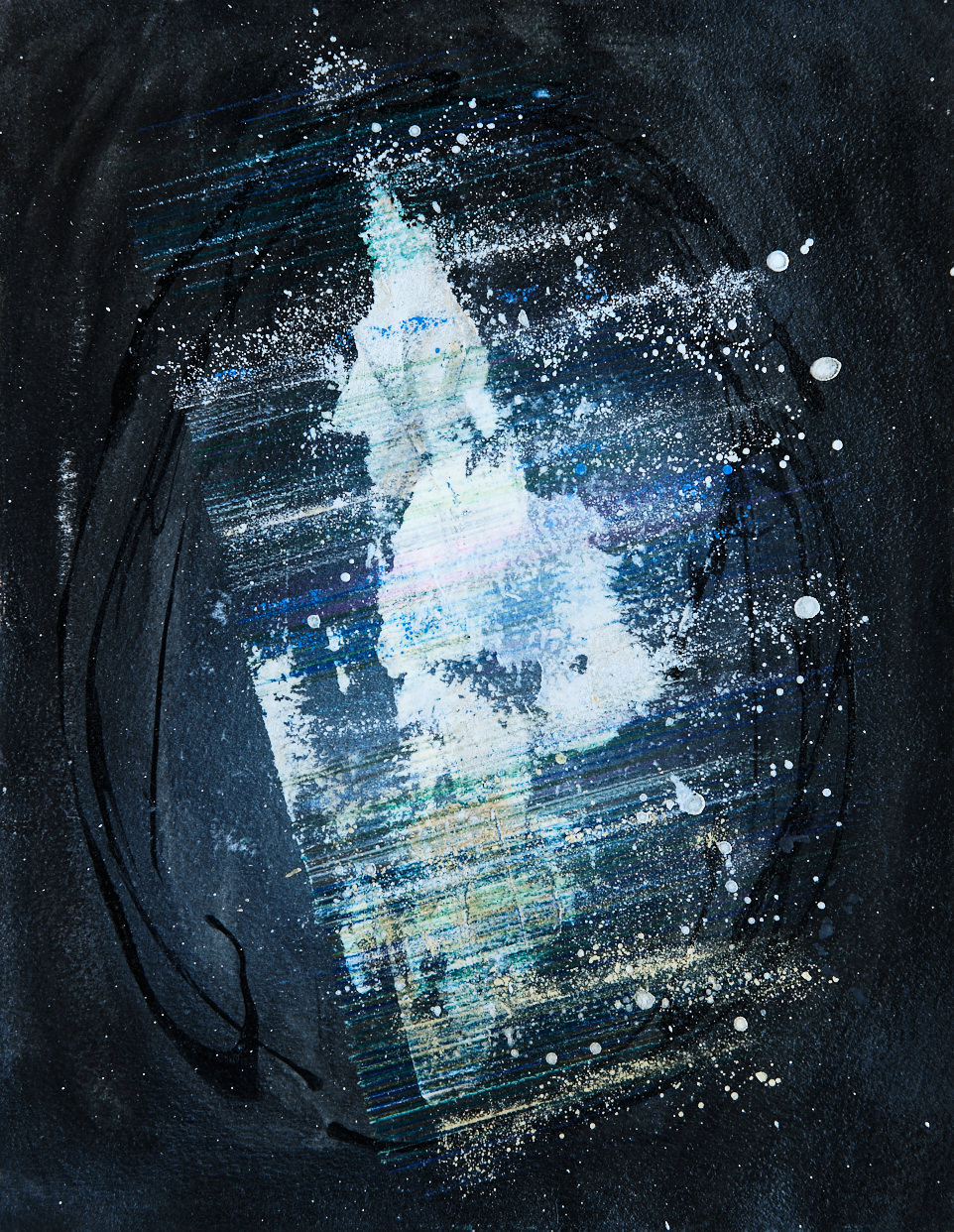

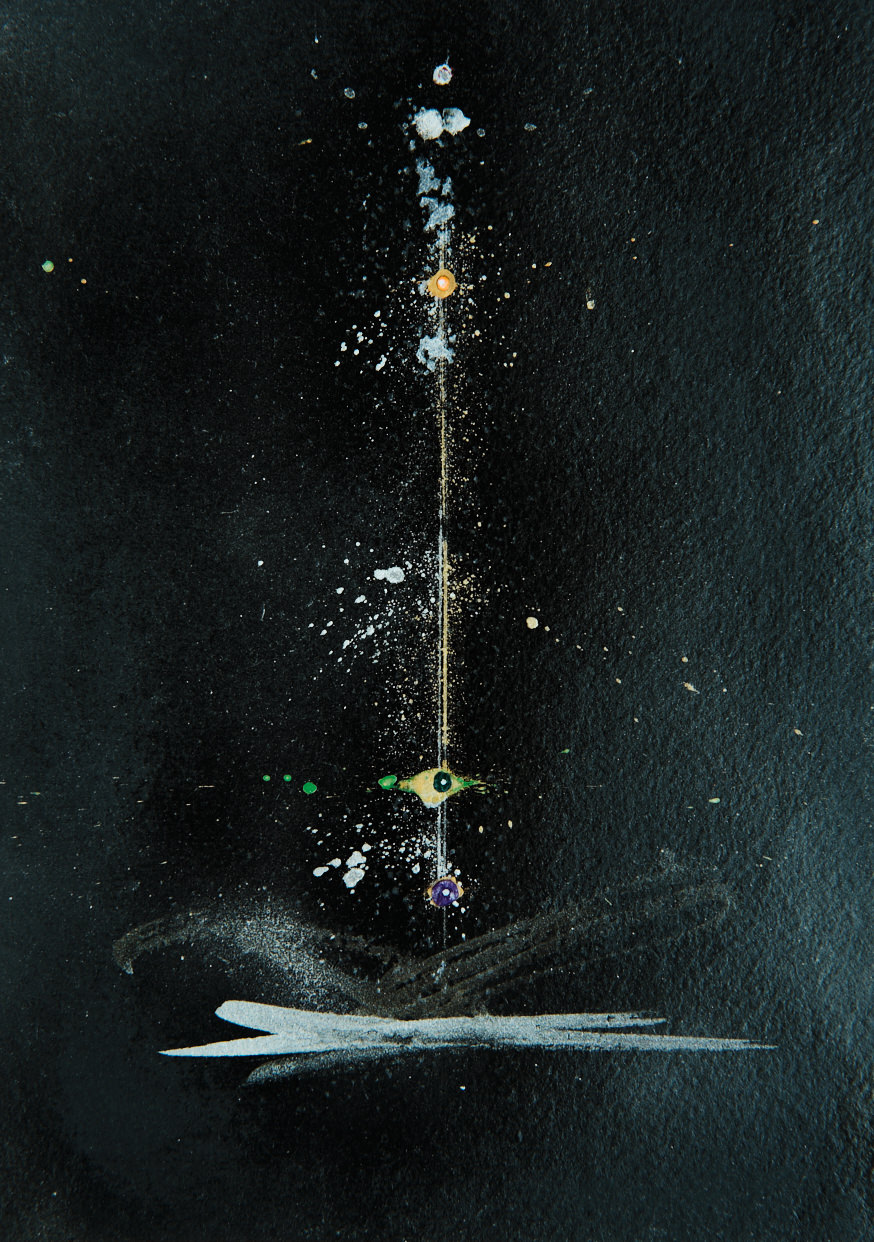

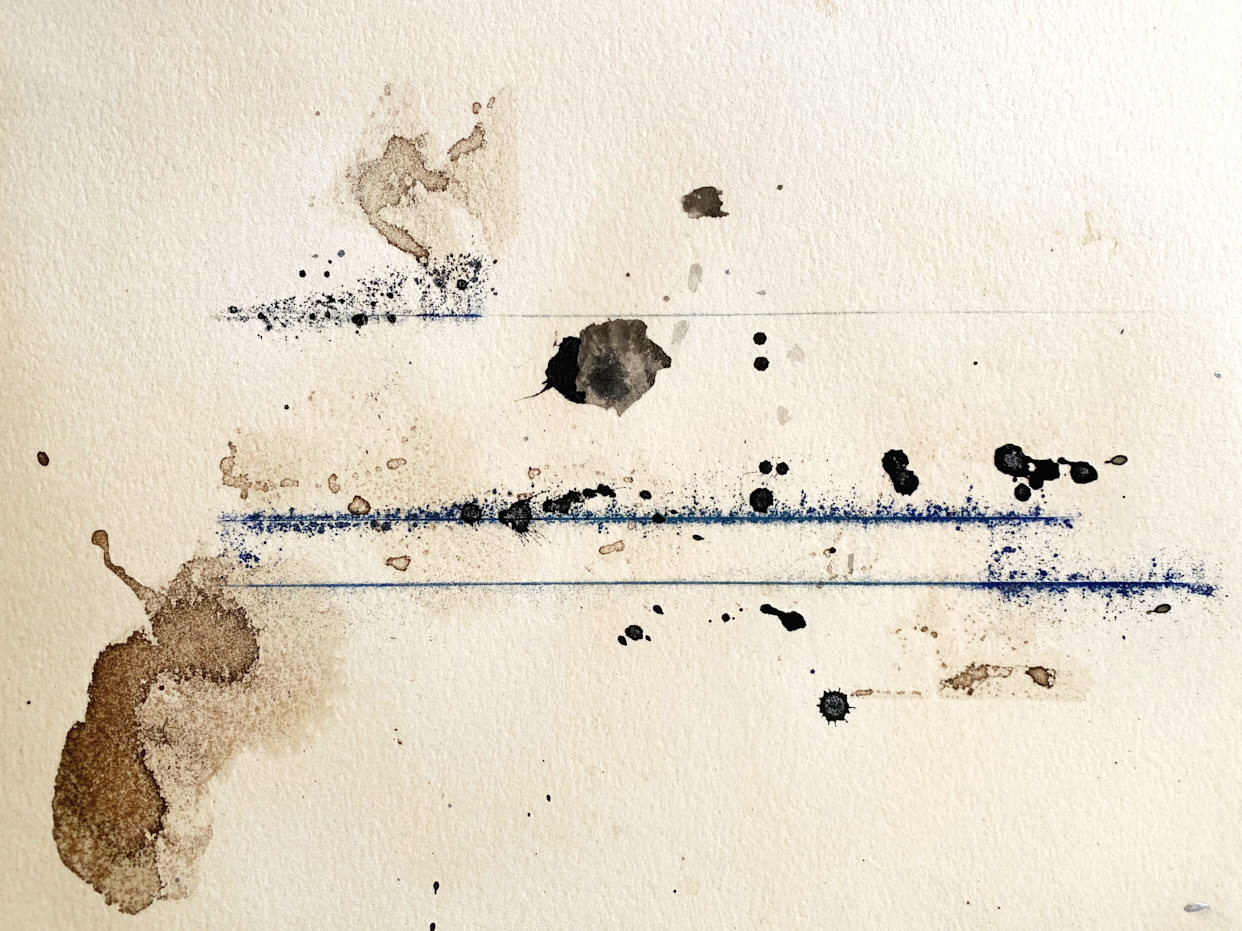

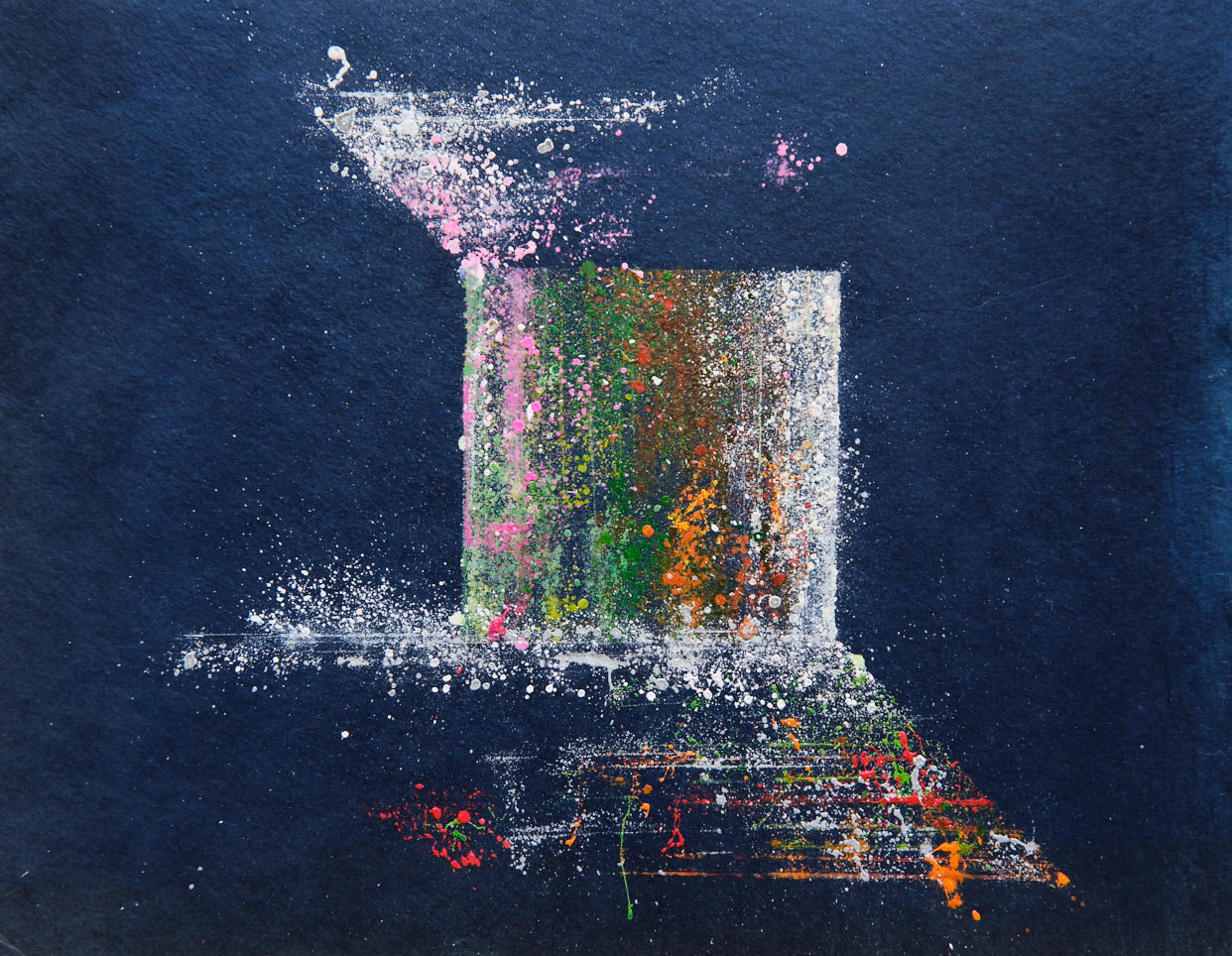

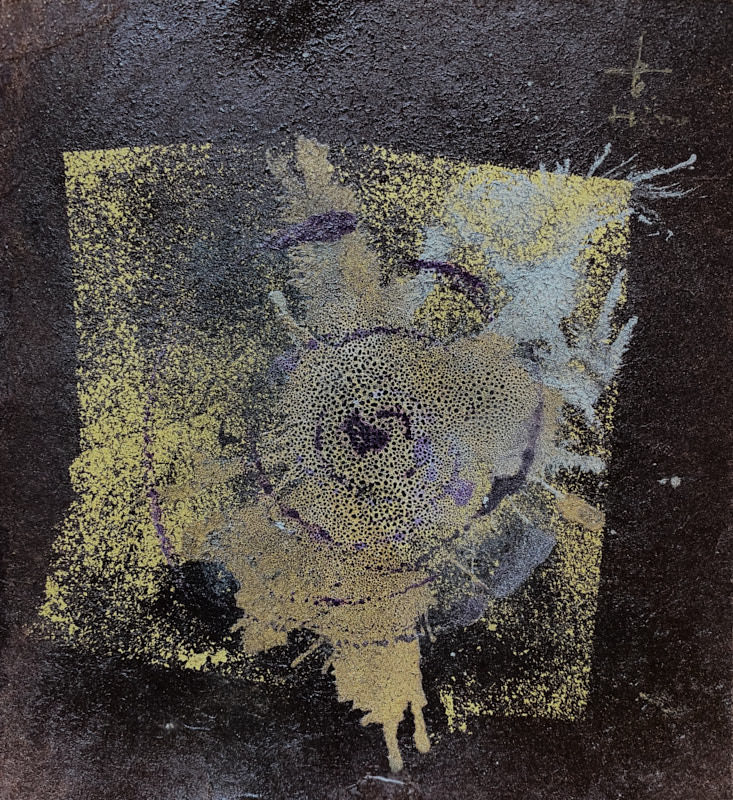

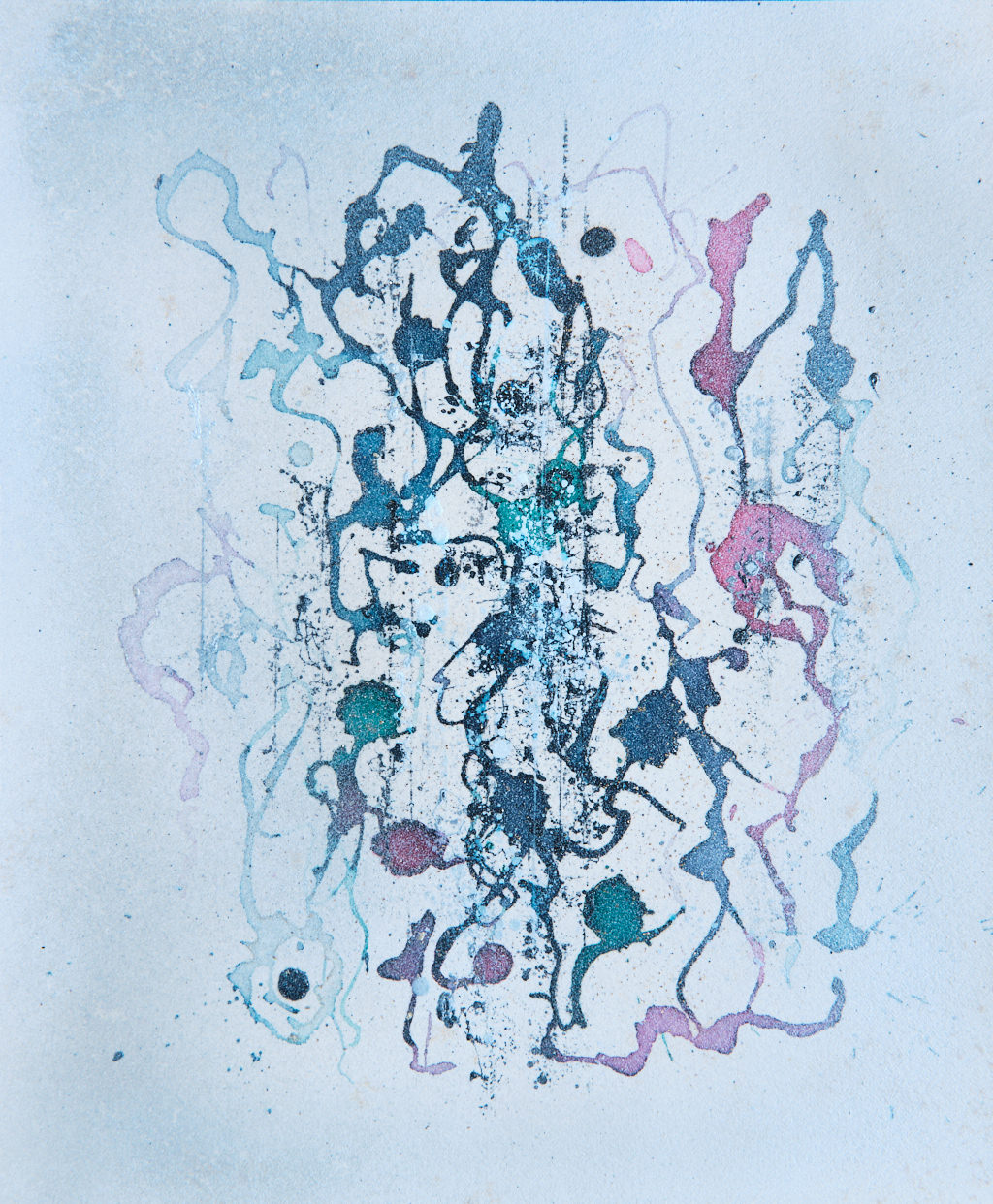

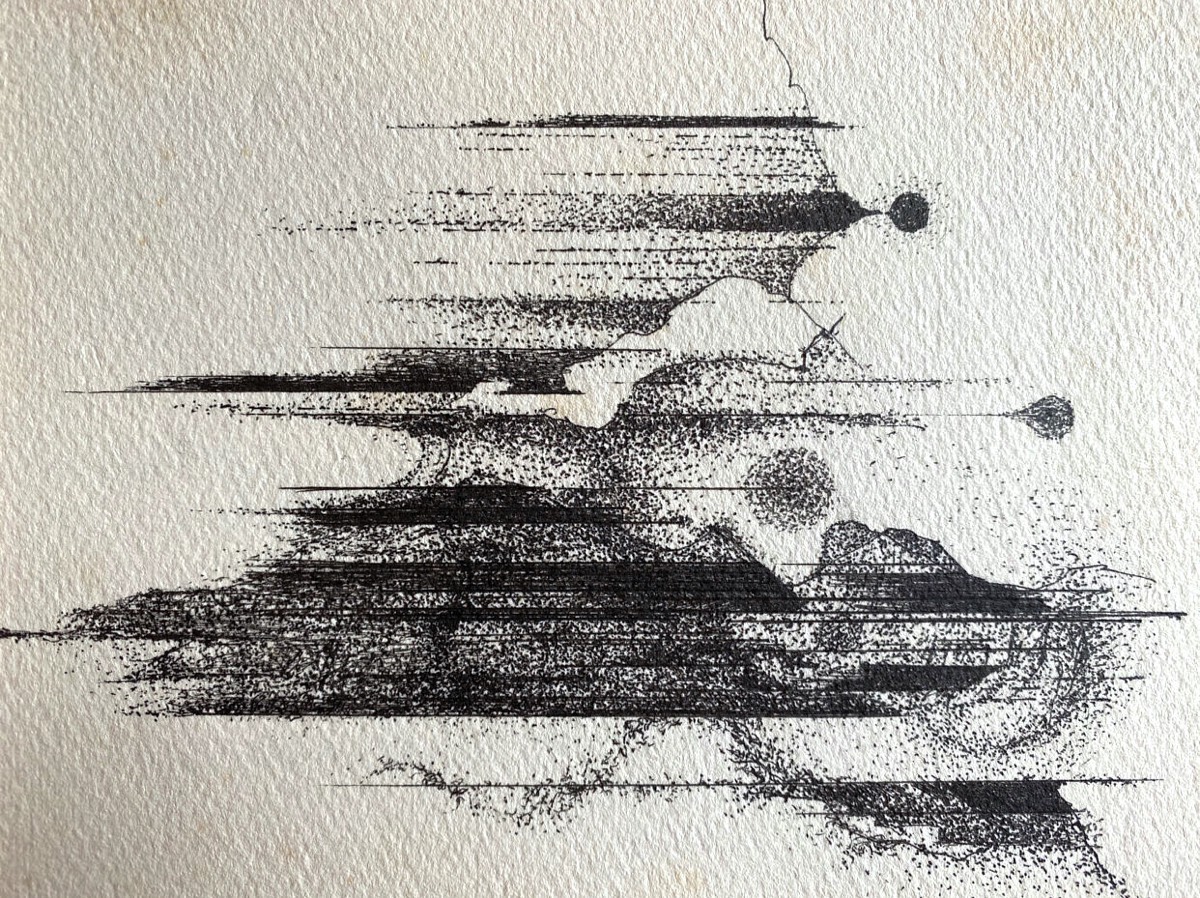

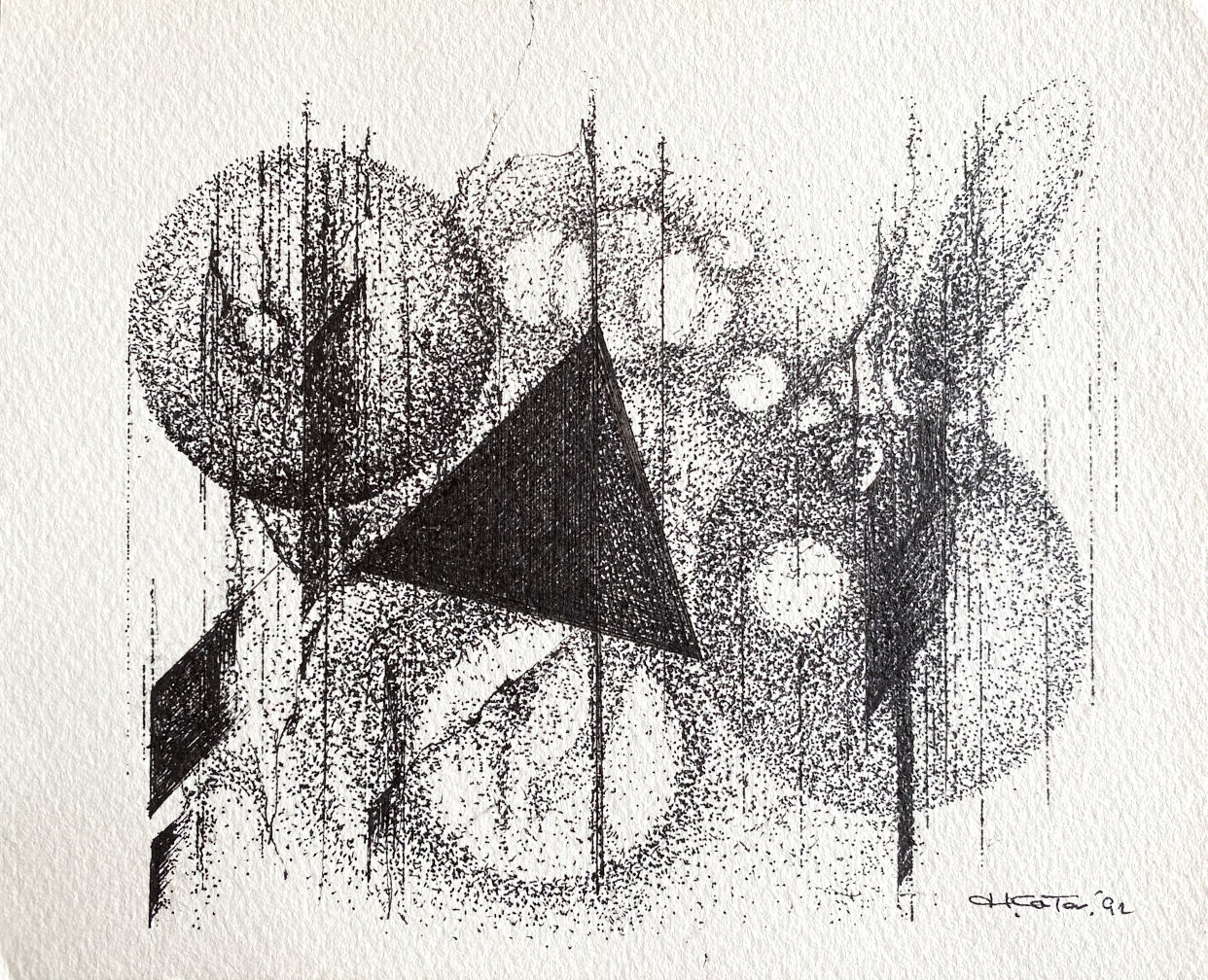

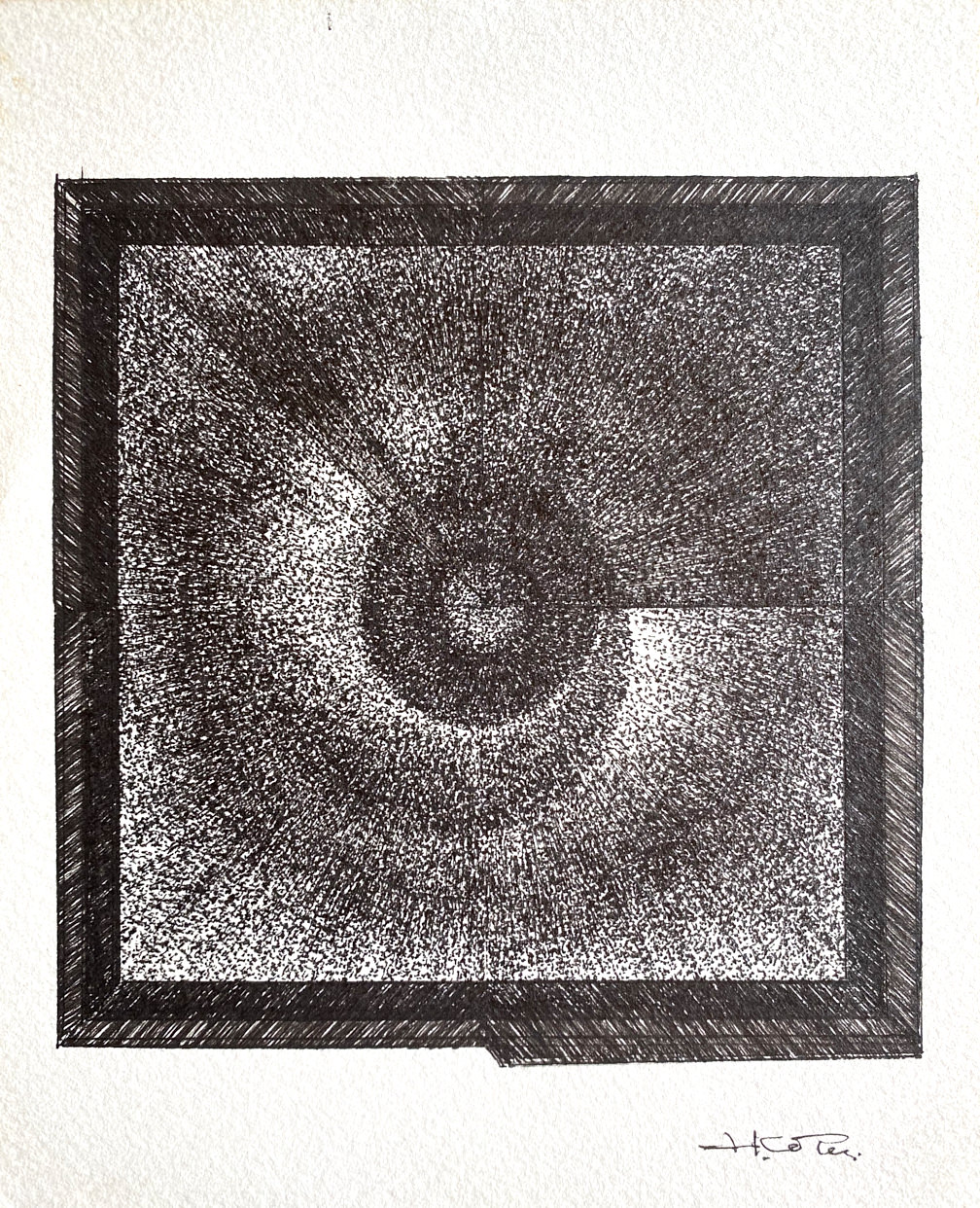

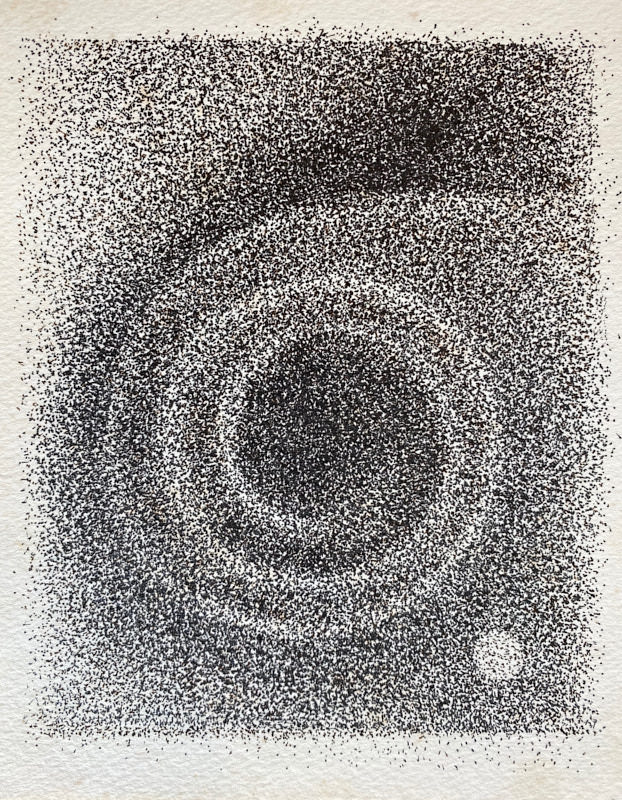

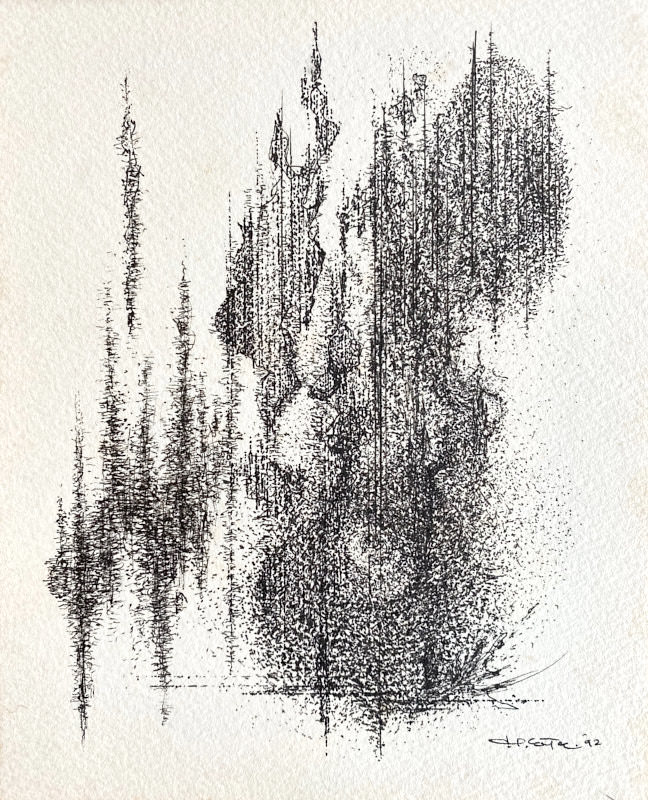

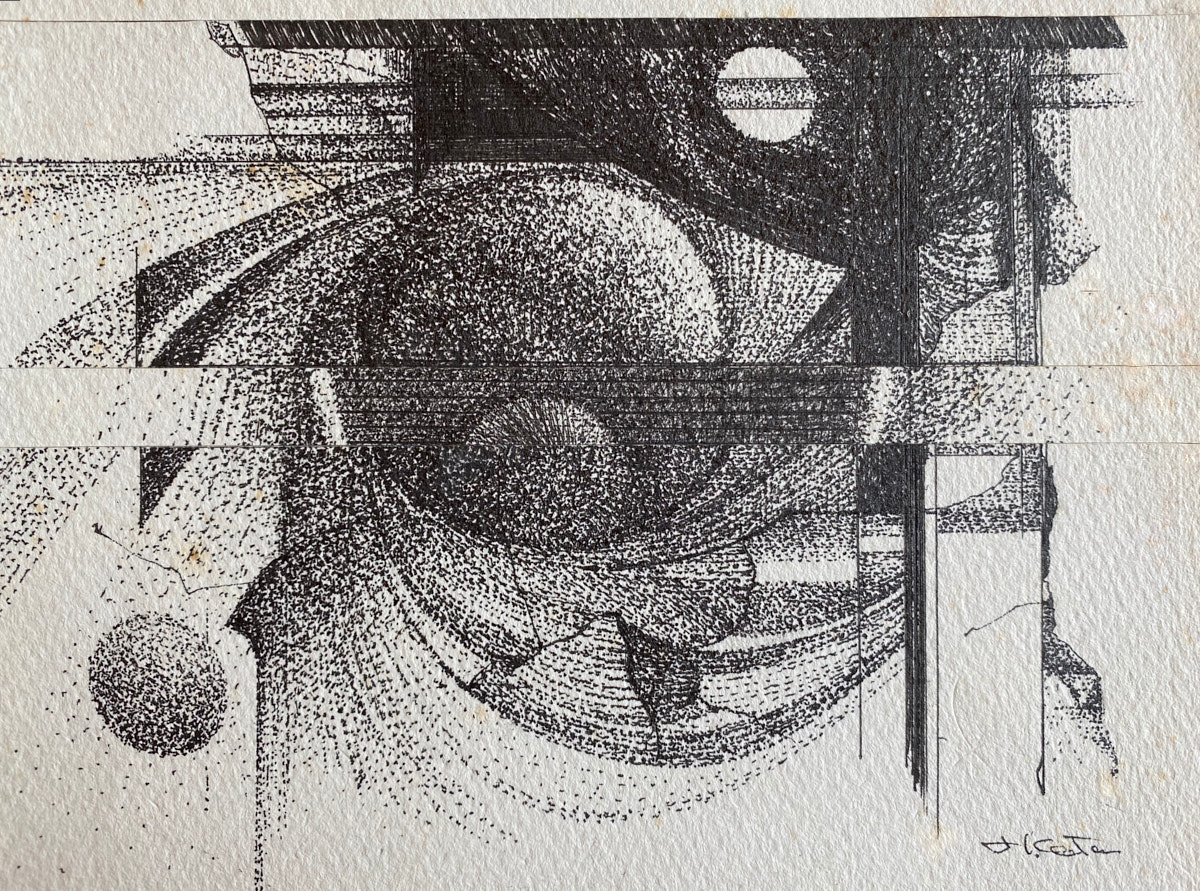

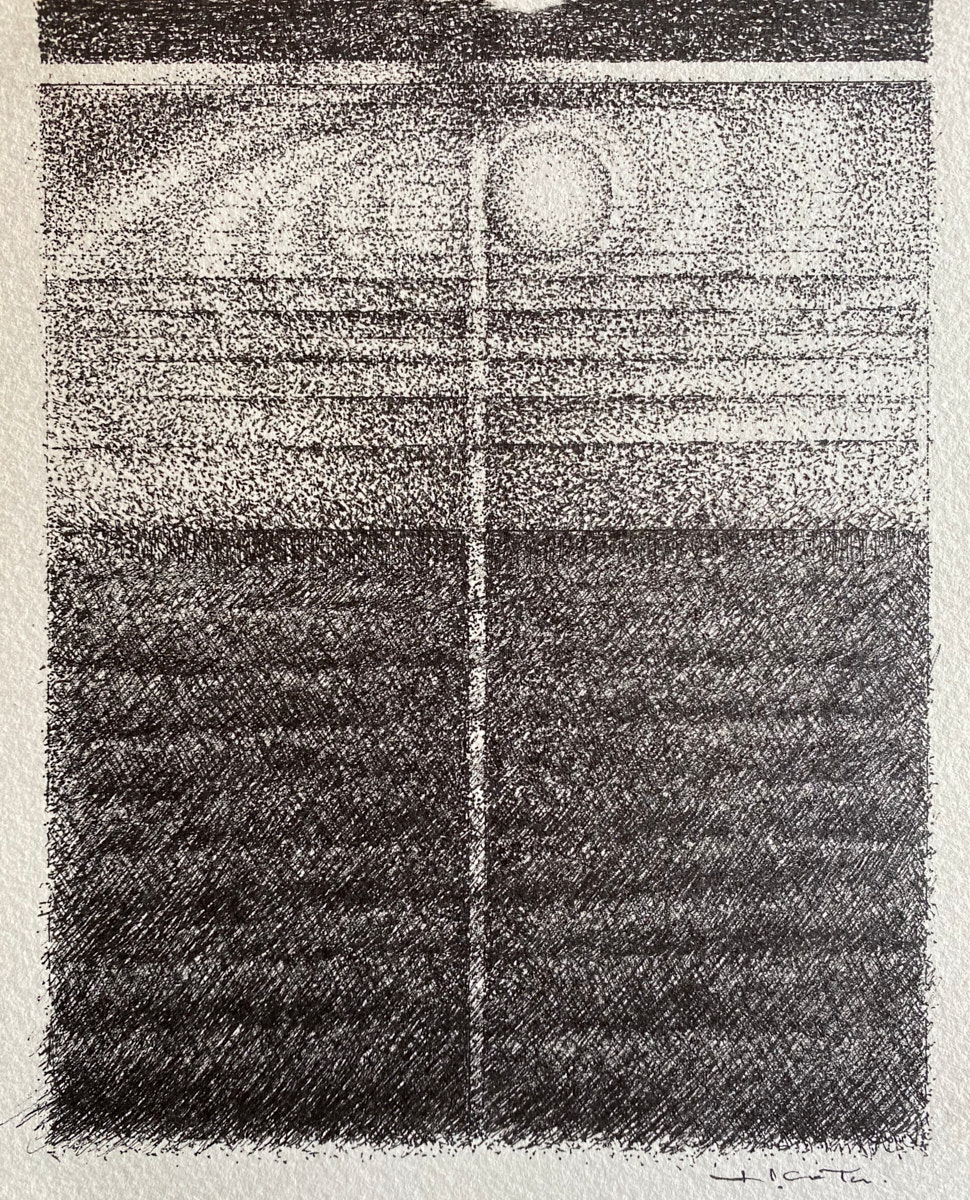

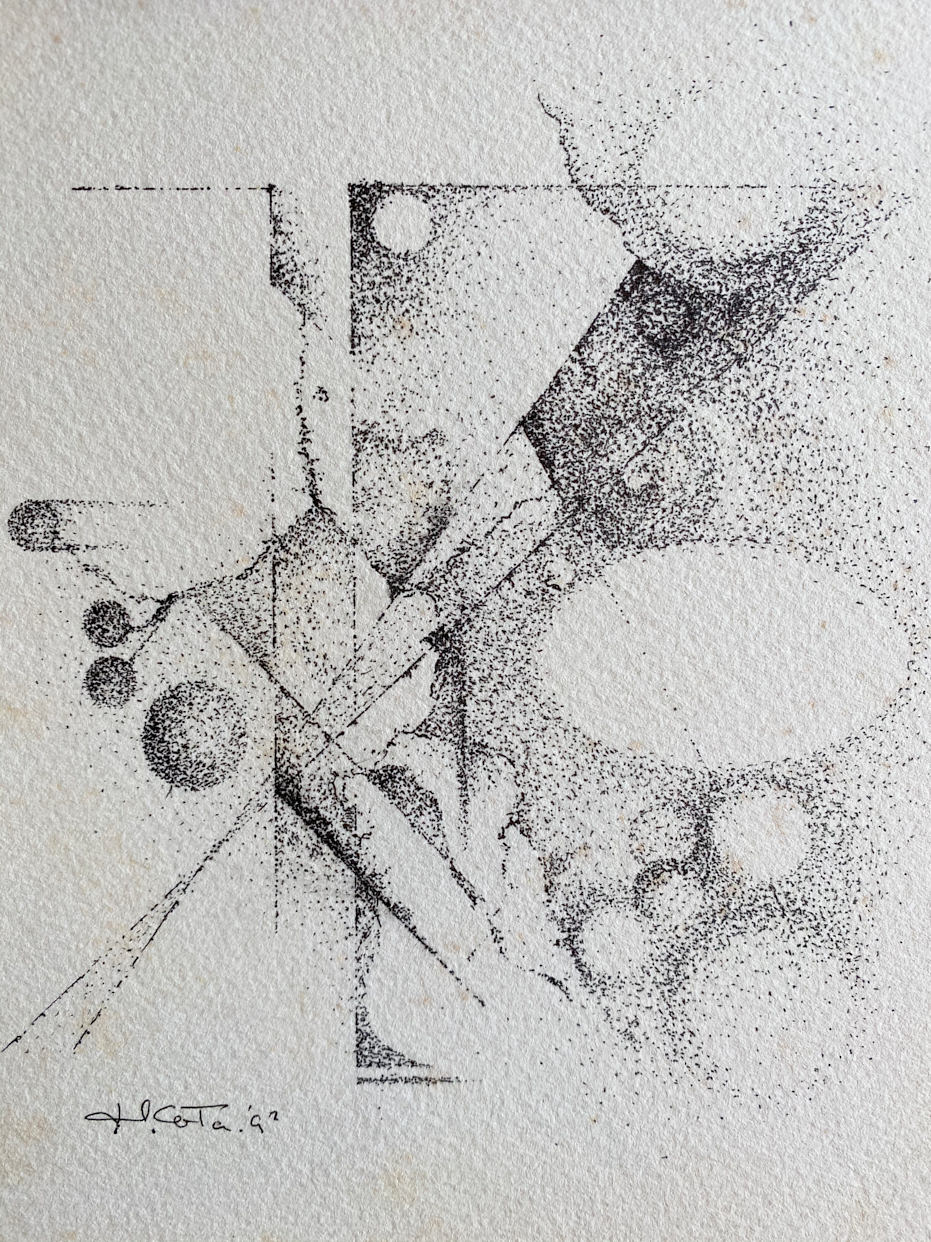

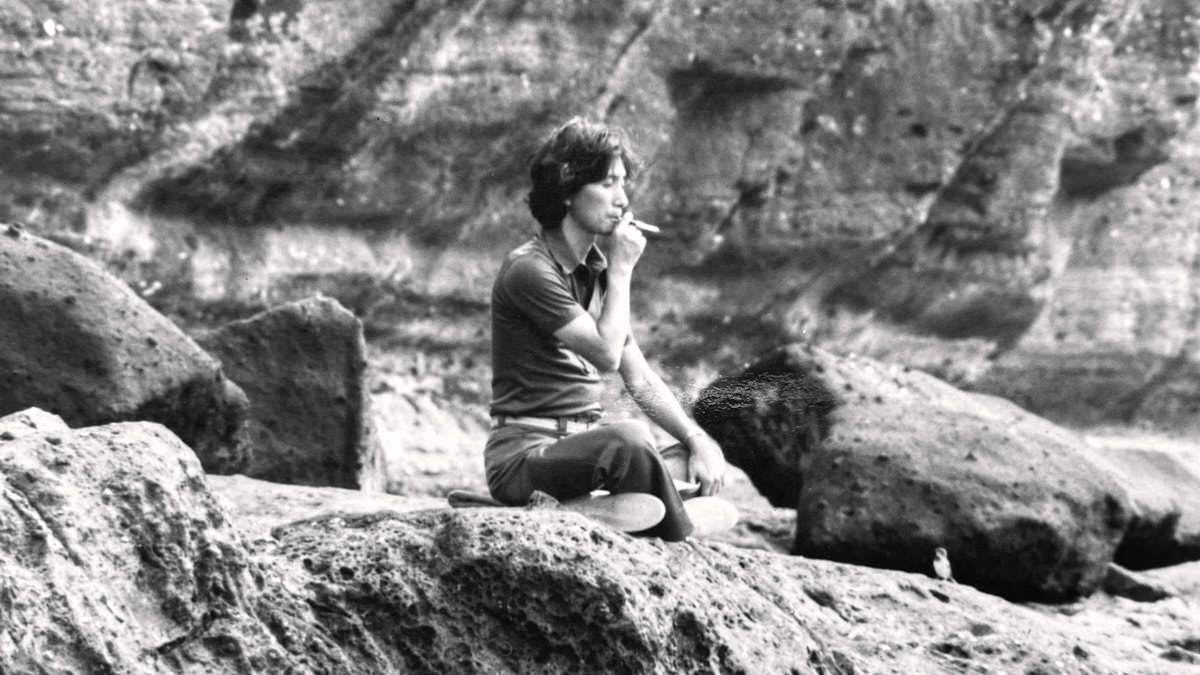

Hiroki Katayama (born Kouki Katayama) started working as an art director while still a student at the Tokyo University of the Arts. Throughout his career in art direction, he received numerous prestigious awards domestically and internationally. But his real passion did not start until much later in life, expressing his unique spiritual experiences through drawings. His themes of drawing are wide in range, and includes Nature, Universe, God, and Spirituality. Though he left this world in 1993 at the age of 56, his paintings had never seen the public light until today. This site features a selection of Hiroki Katayama's art that had been sleeping, untouched, since his death. We invite you to explore the vast and beautiful view of the universe, as seen from within the artist's soul.

- ART WORKS -

MY FATHER HIROKI KATAYAMA

If the memory of my father was a film, the most iconic image of it would be of him at the table in a dark dining room, by a whiskey glass, with his hand still holding a cigarette, his elbow on the table, sleeping. Ashes magically keep the shape of cigarette, its faint smoke still flaring into the air, dancing ephemerally. It would appear as if the only thing alive in the room was this smoke.

This is how I remember my father.

Needless to say, my child heart felt lonely.

Lonely for me. Lonely for him.

My father was quite a successful man. His life was filled with accolades, his record is filled with awards. But at home, he was suffering from a great loneliness. I’ve wondered if it’s because he didn’t have much of a relationship with his own parents. He was raised by his grandparents and didn’t experience much affection while he was young.

The theme of my father’s art may seem varied, but all his works share a common element: they are all deeply spiritual. It seems natural to imagine it is all the reflection of his utter loneliness that he lived with since his childhood. It must have given him a deep insight into life which lead him to question the worth of his existence.

I understand that he was an energetic man at work. He was prolific, won numbers of awards, and was highly regarded internationally. He was loved and always surrounded by many people. As an “art director” for an advertisement agency he was a huge success. He was perceived as a shining star.

But the father I knew was a different man. He spoke in a low voice and barely articulated his words. He didn’t show his emotions but he always looked sad.

In the 1980s, Japan was experiencing a big economic boom and so did the ad agency he worked for. It was what one may call “a golden era”. He had a budget surplus and an ever-growing number of projects; all that one may wish for as an art director in an ad agency.

But to my eyes, it was clear that the more he worked the sadder he became.

I remember the time he started to draw. It was during the time he was at his busiest.

I had started school by this time. After the classes were over, I’d go to his office and find him drawing, painting.

He would usually start drinking in the morning and pass out before sundown.

But on his days off, on weekends, he would wake up early and draw, alone in his office.

When he was 54 years old, he was diagnosed with cancer.

He had developed a serious dependency on alcohol. He discontinued drinking when his cancer treatments began, and this caused him to experience hallucinations.

The last few years of his life, battling cancer, were phenomenally difficult.

But he never let go of his fountain pen and small sketchbook, even in his hospital bed, and kept drawing.

In the twenty-five years since his passing, I must confess that I wasn’t able to truly face who my father was.

The sadness that I felt regarding his self-destructive nature always overwhelmed any sense of pride that I could have been feeling for his creative accomplishments.

I saw him as someone who had lost the battle of life, someone who couldn’t endure the cruelness and ugliness of the world.

A few years ago, my mother passed away out of the blue. It took me by surprise - she was still young. To handle the shock, I told myself that she went to join my father. And this thought led me to revisit his paintings.

Was this my mother guiding me to this? Who knows? But the paintings, which I had seen as expressions of pain, loneliness, of self-harm in darkness, showed me something completely different.

Instead of darkness, I saw light. Instead of beaten, sad and lonely with rejection, I witnessed a wondrous world in which my father actually belonged.

I realized that my father really knew something crucially important.

He knew the essence and the truth of himself.

He was channelling into beauty, the galactic beauty.

How hard it must have been for him to have to shrink and squeeze himself in order to fit into this human world.

My heart vibrated and I wept. I was positively vibrating within this massive world of infinite beauty that he created.

I am so proud of my father.

Aki Kinoshita

(Translated by Yuka C. Honda)

HIROKI KATAYAMA

1937-1993

Audio design by EUCADEMIX(Yuka C. Honda)

Featuring Aki Kinoshita & Nels Cline.

HIROKI KATAYAMA

1937-1993

Artist, Art director

- COLOR PAINTINGS -

- DOT DRAWINGS -

MY FATHER HIROKI KATAYAMA

If the memory of my father was a film, the most iconic image of it would be of him at the table in a dark dining room, by a whiskey glass, with his hand still holding a cigarette, his elbow on the table, sleeping. Ashes magically keep the shape of cigarette, its faint smoke still flaring into the air, dancing ephemerally. It would appear as if the only thing alive in the room was this smoke.

This is how I remember my father.

Needless to say, my child heart felt lonely.

Lonely for me. Lonely for him.

My father was quite a successful man. His life was filled with accolades, his record is filled with awards. But at home, he was suffering from a great loneliness. I’ve wondered if it’s because he didn’t have much of a relationship with his own parents. He was raised by his grandparents and didn’t experience much affection while he was young.

The theme of my father’s art may seem varied, but all his works share a common element: they are all deeply spiritual. It seems natural to imagine it is all the reflection of his utter loneliness that he lived with since his childhood. It must have given him a deep insight into life which lead him to question the worth of his existence.

I understand that he was an energetic man at work. He was prolific, won numbers of awards, and was highly regarded internationally. He was loved and always surrounded by many people. As an “art director” for an advertisement agency he was a huge success. He was perceived as a shining star.

But the father I knew was a different man. He spoke in a low voice and barely articulated his words. He didn’t show his emotions but he always looked sad.

In the 1980s, Japan was experiencing a big economic boom and so did the ad agency he worked for. It was what one may call “a golden era”. He had a budget surplus and an ever-growing number of projects; all that one may wish for as an art director in an ad agency.

But to my eyes, it was clear that the more he worked the sadder he became.

I remember the time he started to draw. It was during the time he was at his busiest.

I had started school by this time. After the classes were over, I’d go to his office and find him drawing, painting.

He would usually start drinking in the morning and pass out before sundown.

But on his days off, on weekends, he would wake up early and draw, alone in his office.

When he was 54 years old, he was diagnosed with cancer.

He had developed a serious dependency on alcohol. He discontinued drinking when his cancer treatments began, and this caused him to experience hallucinations.

The last few years of his life, battling cancer, were phenomenally difficult.

But he never let go of his fountain pen and small sketchbook, even in his hospital bed, and kept drawing.

In the twenty-five years since his passing, I must confess that I wasn’t able to truly face who my father was.

The sadness that I felt regarding his self-destructive nature always overwhelmed any sense of pride that I could have been feeling for his creative accomplishments.

I saw him as someone who had lost the battle of life, someone who couldn’t endure the cruelness and ugliness of the world.

A few years ago, my mother passed away out of the blue. It took me by surprise - she was still young. To handle the shock, I told myself that she went to join my father. And this thought led me to revisit his paintings.

Was this my mother guiding me to this? Who knows? But the paintings, which I had seen as expressions of pain, loneliness, of self-harm in darkness, showed me something completely different.

Instead of darkness, I saw light. Instead of beaten, sad and lonely with rejection, I witnessed a wondrous world in which my father actually belonged.

I realized that my father really knew something crucially important.

He knew the essence and the truth of himself.

He was channelling into beauty, the galactic beauty.

How hard it must have been for him to have to shrink and squeeze himself in order to fit into this human world.

My heart vibrated and I wept. I was positively vibrating within this massive world of infinite beauty that he created.

I am so proud of my father.

Aki Kinoshita

(Translated by Yuka C. Honda)

©︎ 2020 Hiroki Katayama Artworks